Was the Electric Chair Invented by a Dentist? Debunking the Popular Myth

Ever heard someone say, “Did you know the electric chair was invented by a dentist?” If you’ve come across this claim at a trivia night or when reading weird stories online, you’re not alone. The story is hard to forget—a dentist, of all people, coming up with something as dark as the electric chair! But is it really true? Is there a real tie between dentistry and this famous execution device? Today, let’s clear up the confusion, see how the electric chair was invented, and break down a bit of the history mixed up with science, ethics, and some memorable people.

In This Article

- The Short Answer: No, But a Dentist Had the Original Idea

- Who Was Alfred P. Southwick?

- Southwick’s Plan: Trying to Make Execution Kinder

- Who Actually Built the Electric Chair?

- Edison, Westinghouse, and the “Current Wars”

- The First Execution: Kemmler, Problems, and Complaints

- The Electric Chair’s Legacy (and What Came Next)

- What This Story Teaches Us

- Key Takeaways and Things to Do

The Short Answer: No, But a Dentist Had the Original Idea

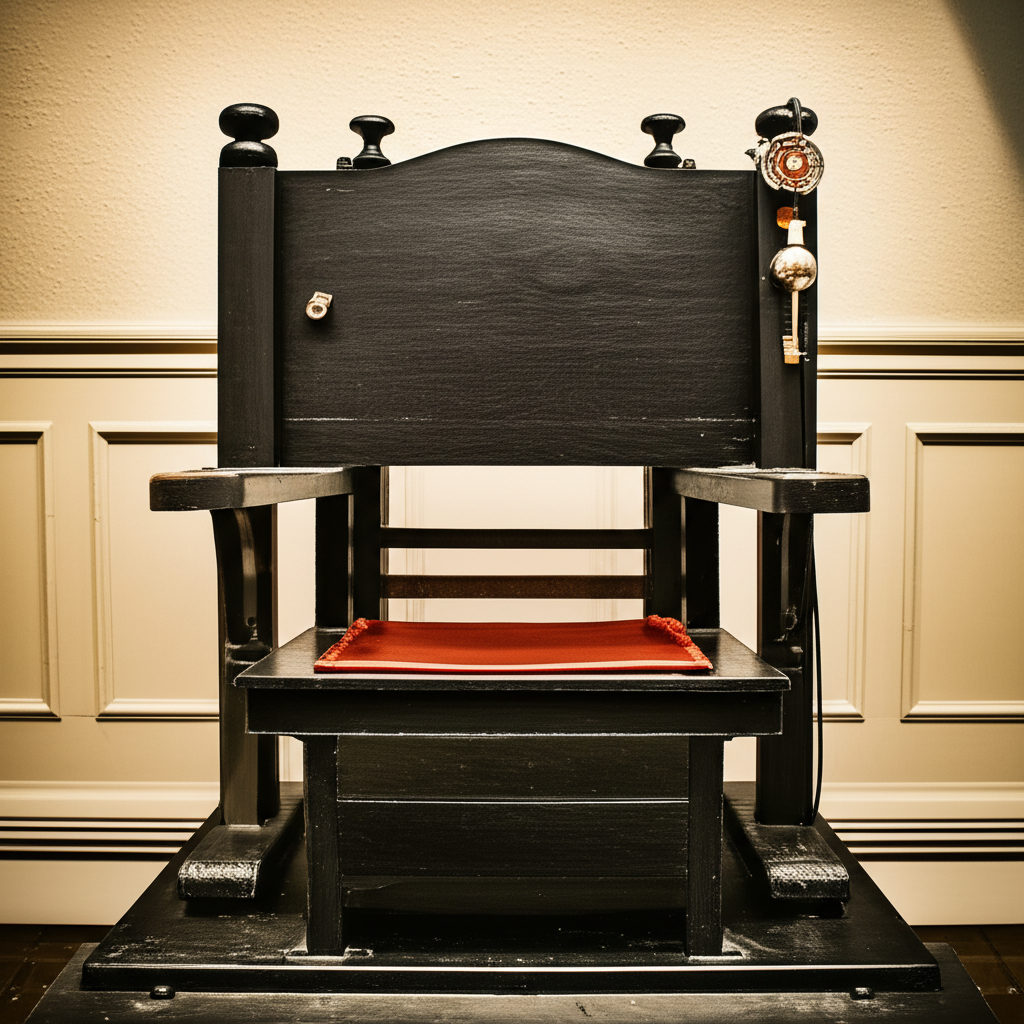

Let’s get to the point: A dentist did not invent the electric chair—at least, not the way most people think. The person who really designed and built the chair was Harold P. Brown, an electrical engineer, along with others at a time when America’s electric industry was getting huge. However, there is a little bit of truth in the popular myth. Alfred P. Southwick, a dentist from Buffalo, New York, played a big part in thinking up electrocution as a “kinder” way to execute people instead of hanging.

So where did this story even start? Let’s take a closer look.

Who Was Alfred P. Southwick?

You might be picturing someone in a white coat, working on teeth. That’s pretty much it. Alfred P. Southwick was a dentist, but he was also a teacher, inventor, and local leader in Buffalo in the late 1800s.

From Accident to New Idea

One night in 1881, Southwick saw something shocking—an older man who was drunk touched a live electric wire by accident and died right away. The man’s death looked quick and, to people watching, not violent. This moment made Southwick wonder: could electricity do the job of execution in a better way?

At that time, public hangings were common, often messy, and sometimes went very badly. People were looking for a “nicer” way—a method that didn’t go wrong or turn into a scary show.

More Than Just an Observer: Southwick’s Work

Southwick didn’t just mention his idea to a friend and stop there. He kept talking about this new, electric way to execute. He wrote about it, gave talks, and was picked to join the New York State Commission on Capital Punishment (a group trying to find a better way than hanging). Southwick’s message was clear: with the right control, electricity could cause a quick death with less pain or spectacle.

Southwick’s Plan: Trying to Make Execution Kinder

Trying to make execution “kind” sounds strange today, but back then, people thought it was a real problem. Here’s how Southwick helped push his idea from a weird accident to a new state policy.

Working With Doctors, Engineers, and Lawmakers

The Commission brought together doctors, engineers, lawyers, and Southwick. Their big goal: look at all the types of executions—hanging, shooting, poison gas, and more.

- Southwick used his science and medical knowledge to argue that electricity could shut down the body quickly.

- He said electric death was less violent—no ropes, no messy machines. He thought it would be more respectful.

- The Commission finally chose electrocution as the “kindest” option—mainly because Southwick really pushed for it.

But when it was time to actually make the machine, that job went to the electrical engineers.

Who Actually Built the Electric Chair?

Think of America in the late 1880s—electric lights were just coming in, and people were nervous about what electricity could do. That’s when Harold P. Brown, an engineer, and a group of important electric company bosses stepped in.

Harold P. Brown—From Idea to Machine

Brown wasn’t just a lab worker. He was an engineer who knew how to get noticed—he even teamed up with Thomas Edison. Edison liked direct current (DC), but George Westinghouse was selling alternating current (AC). Edison and Brown wanted to prove that AC wasn’t just dangerous—it could actually kill.

Brown showed this by electrocuting animals in public, using AC. These shows weren’t just for fun. Brown worked with prison leaders, doctors, and scientists to figure out the exact amount of electricity to use for an execution. He built the first electric chair, adding electrodes, straps, and switches for the people running the machine.

- Truth: Brown, not Southwick, made the chair and did the hard science work.

- Brown’s design became the model for later electric chairs.

Edison vs. Westinghouse: Business Fights and Scary Shows

Why did Edison care about the electric chair? He wanted to hurt his rival Westinghouse’s business! If everyone thought AC power could kill, maybe they wouldn’t use it in their homes or factories.

Westinghouse didn’t like this and paid for lawyers to try to stop the first electric chair killing. But Edison and Brown’s efforts worked, and New York went forward with the AC electric chair.

Edison, Westinghouse, and the “Current Wars”

The United States in the 1880s was interested in everything electric. Lightbulbs, streetcars, and home power were just getting started.

What Were the Current Wars?

- Thomas Edison wanted to use direct current (DC) because it was safer for short wires but needed many more stations.

- George Westinghouse liked alternating current (AC), which could travel farther.

Edison said AC was so dangerous it could kill you suddenly, and he used the electric chair to prove his point. The “Current Wars” were a fight not just about science, but about who would make more money and look better in the papers.

Trying to Make Execution Nicer—or Just a Dirty Trick?

Remember: on top of all the “progress,” there was a lot of politics, business, and even sneaky tricks involved. Even the idea of a “good” execution was used to help big companies win a fight.

The First Execution: Kemmler, Problems, and Complaints

Now, picture this: August 6, 1890, in Auburn Prison, New York. The first use of the electric chair was big news all over the country.

William Kemmler: The First Test

William Kemmler, who was found guilty of killing someone, was the first to face the electric chair. The plan? Strap him in, zap him with electric current, and let him die quickly and painlessly.

But what really happened?

- The first electric shock didn’t kill him.

- The second shock was much stronger. It burned him, and the smell was horrible.

- Reporters and witnesses were sickened. One said it was “worse than hanging.”

This bad start caused lots of anger—was this really kinder, or just another horrible way to die? Even so, the electric chair became the main way for quite some time.

The Electric Chair’s Legacy (and What Came Next)

After Kemmler, other states copied New York’s idea. For most of the early 1900s, the electric chair was America’s main way to do executions.

How Did It Spread?

- Small fixes: Engineers changed things like the voltage and made better straps and controls.

- Hundreds executed: In the 1900s, thousands died this way in states all over the country.

- More complaints: People who hated the death penalty used stories like Kemmler’s to push for change.

Why Did We Leave the Electric Chair Behind?

As science, medicine, and people’s feelings changed, lethal injection was brought in—said to be even “kinder” and easier to control. Today, the electric chair is almost never used—only a few states still allow it as a backup.

If you’re interested in how the story of electricity connects with new dental technology today, this same kind of new thinking can be found in digital dental lab work and the goal of better, kinder care in medicine.

What This Story Teaches Us

Let’s take a step back. This isn’t just a weird old story or a fact to share at Halloween. What does this really show us? It’s about how new ideas start, how science and right-and-wrong can get mixed up, and how “progress” is never simple. Trying to find a “better” way to do something hard—like executions—shows us a lot about fear, pain, and even fairness. And it shows how rumors can spread or get twisted.

Some things jump out:

- Anyone—even a dentist—can play a big role in changing history.

- Big changes need a team: inventors, builders, lawmakers, and dreamers.

- Each new invention shows us what people were worried about, cared about, or even fighting over at the time.

Even today, science keeps pushing things forward. In dentistry, for example, people always look for new ways to make things easier or less scary for patients. Whether it’s making better dental crowns, new materials, or helping people with missing teeth using an implant dental laboratory, the same drive for a “kinder” solution is there—except now, it’s about saving smiles.

Key Takeaways and Things to Do

Let’s finish with a quick review and ideas for what you can do with stories like this.

Main Points to Remember

- Alfred P. Southwick, a dentist, did not invent the electric chair itself, but he thought of using electricity for execution after seeing an accident.

- Harold P. Brown, an engineer, really built the chair, working with Thomas Edison—who wanted to use it in his business fight with George Westinghouse in the “Current Wars.”

- The New York State Commission on Capital Punishment backed Southwick’s idea, trying to find a “kinder” way than hanging.

- The first real use, on William Kemmler, was so bad it made world news and started a debate that hasn’t stopped.

- The electric chair was later replaced by lethal injection as the push for an easier, less painful way went on.

If You’re Interested… or Worried

- Check your facts. If you hear a weird “fact” about teeth, science, or history, look it up. Rumors can start with a little truth but get changed.

- Ask someone who knows. If you ever have questions about your own health—especially with dentistry, which can be scary—reach out to a good dentist or expert.

- See the good in new ideas. The push for “better” that helped Southwick and Brown is still here. Whether you want better crowns, night guards, or something from a removable denture lab, today’s new solutions exist because people keep trying new things.

A Few More Fascinating Questions (and Their Answers!)

Was the electric chair really kinder than hanging?

Back then, people said yes, but in reality, it was not always so simple. Some electric chair executions went okay, others went very wrong. It shows the ongoing talk about what “kind” really means.

Is the electric chair still used?

Not much at all. Most states use lethal injection, and only a few keep the electric chair as an option.

Does dentistry have other weird connections with history?

You might be surprised! Dentistry has a strange and interesting past, from George Washington’s false teeth to big jumps in pain-free care.

Your Healthy Takeaway—What To Do Next

This story is more than just a creepy fact. It’s proof that big changes can start in strange places. A dentist’s thought, an engineer’s machine, and a lot of business fights changed American history.

The real lesson? Being creative, thinking hard, and caring about people are always important, in dentistry and everywhere else. If you want to see how today’s smart, caring experts use new tech to make things safer and better, check out a good china dental lab for the latest dental solutions, or see what a good guide to dental care can offer you for the long term.

Remember: When you hear a myth about teeth, doctors, or inventions, don’t just believe it. Ask questions and you might learn something really interesting.

Smile bravely, stay curious, and keep learning—because even the weirdest facts can teach us, and your own health is worth the search!

References:

- American Dental Association

- New York State Archives

- National Museum of American History

- “Execution by Electrocution: The Invention of the Electric Chair” by Edwin F. Davis

- Smithsonian Magazine, “The Shocking Story of the Electric Chair”

(This article has been checked by a dental expert for correctness.)